Innovative research shows how the stave churches may have been built

Publisert 01.06.2021

Publisert 01.06.2021

By Andrij Kutnyi/Chair of Building History, Building Archaeology and Conservation, Department of Architecture, Technical University of Munich

Click here to explore the researchers' 3D-model of Borgund Stave Church

The main goal of the project "Building research at the oldest European wooden churches" was the digital acquisition and scientific investigation of some stave churches. A work team of graduates and students led by Dr. Andrij Kutnyi, the Technical University of Munich (TUM), devoted three years to researching the buildings. The project was selected and funded as part of a program to support building research subject of the German Ministry of Education and Research.

This video provides an overview of the project:

Stave churches with an elevated central nave

One important task in the project was the investigation of the stave churches using modern methods of building research and the reconstruction of the building history using the latest knowledge.

A total of 28 preserved Norwegian stave churches were selected for the project in collaboration with the Norwegian Directorate of Cultural Heritage (Riksantikvaren) and the National Trust of Norway (Fortidsminneforeningen).

The focus of the investigations are representatives of stave churches of a similar type, namely the churches in Hopperstad (around 1131), Kaupanger (1183/84), Borgund (1180/81) and Lom (1160, 1634/63). These three belong typologically to the building type of stave churches with an elevated central nave.

Digital floor plan of Borgund Stave Church. © Andrij Kutnyi

Surveying the stave churches' building history

Over the centuries, the stave churches were frequently rebuilt and repaired. After a review of the later building phases, the structural development of this type of stave church is presented in a comparative analysis.

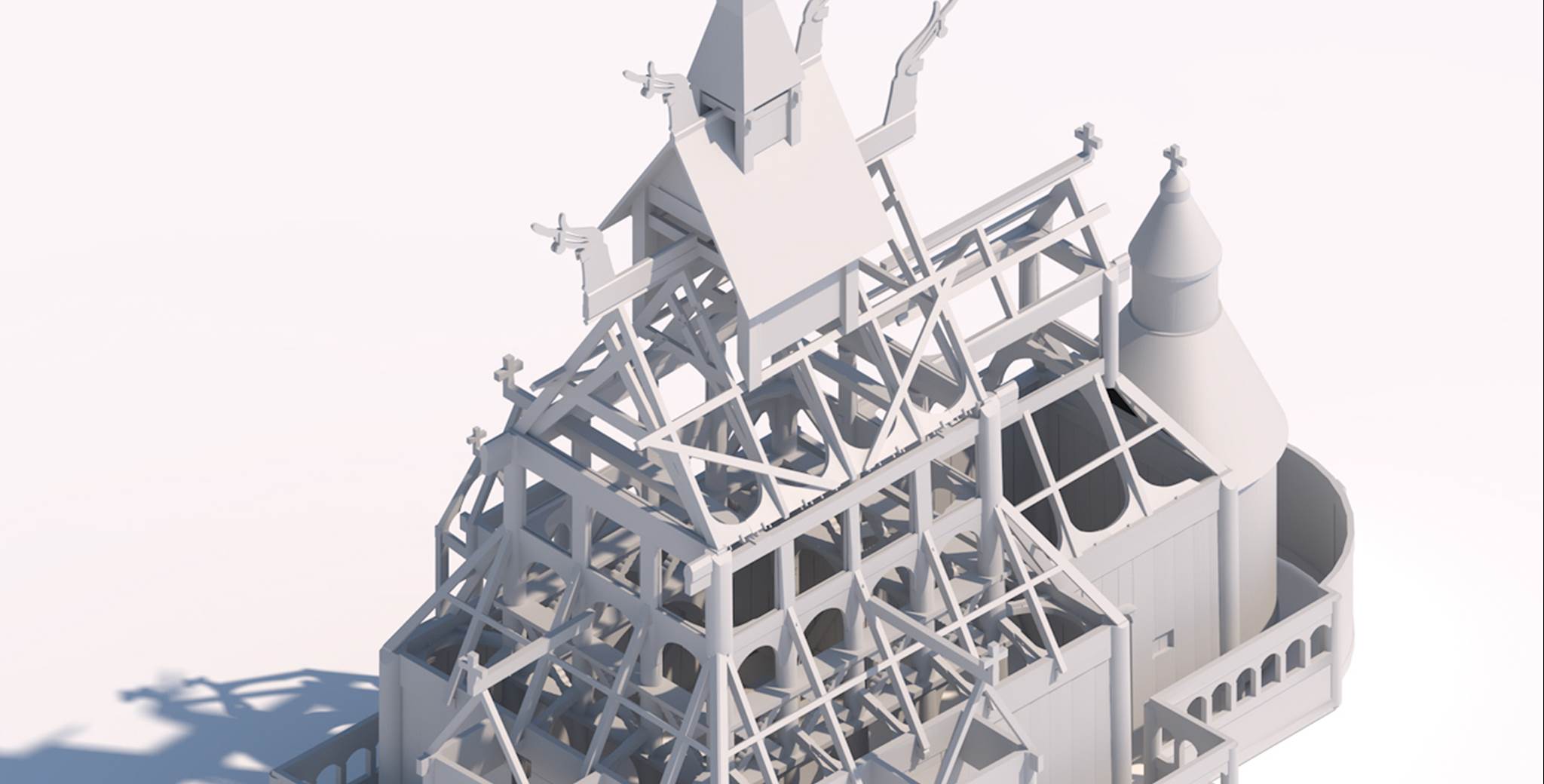

The development was illustrated by digital spatial models. For this purpose, detailed digital measurements of the construction from the sill to the roof were carried out in each church. Modern stocktaking technologies and their visualization in detailed 3D models help to make the objects and the scientific results easily accessible not only to specialists, but also to interested non-specialists. This is intended to raise awareness of the varied architectural history of the stave churches and thus preserve these important monuments.

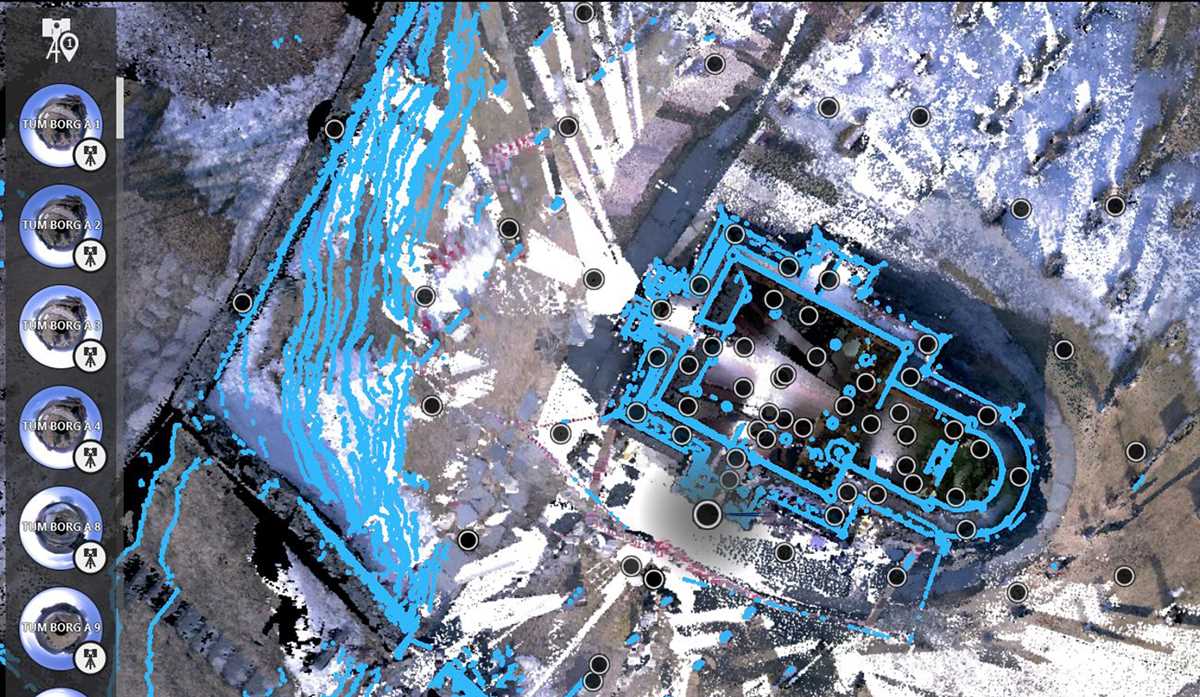

Map of the stave church of Borgund. The black dots show the location of the scanner stations. © Andrij Kutnyi

Scanning and 3D-models

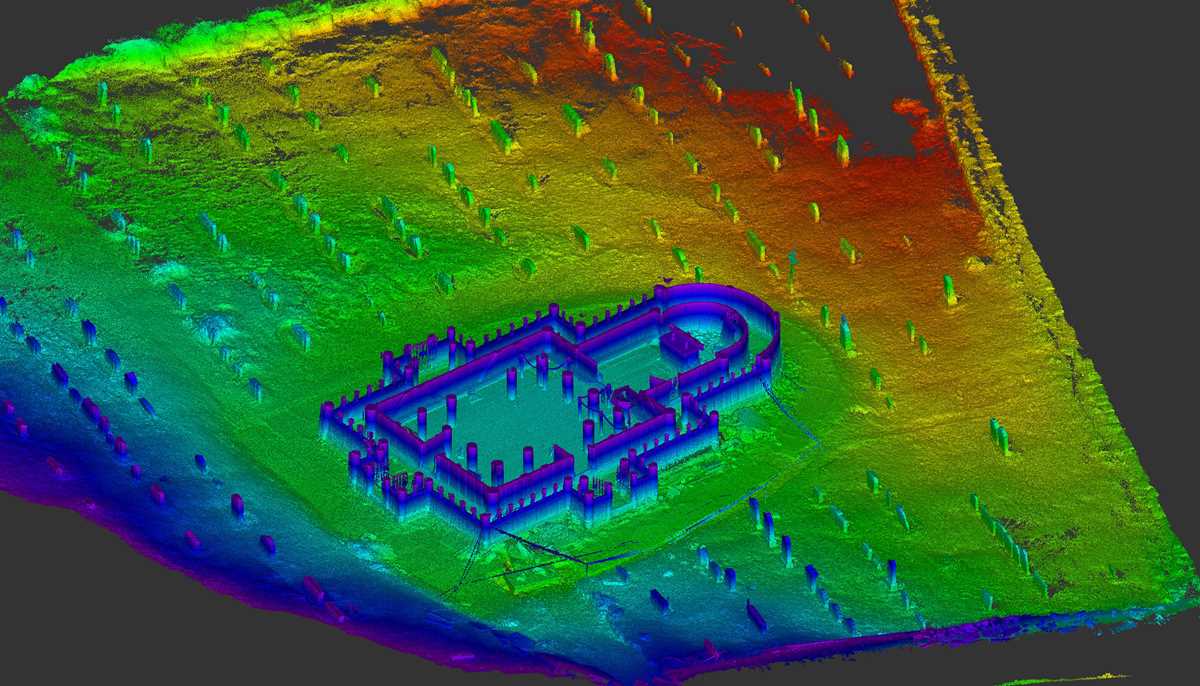

In the research campaigns from April 2018 to October 2019, the stave churches were measured and scanned. During this time, a team of four researchers from the Technical University of Munich worked on the detailed investigations of the buildings. For each church, the work took about 20 days on site in Norway and four months at the computer workstations in the university office. The entire building geometry and volume as well as decorative elements were recorded with a laser scanner. For this purpose, each church was precisely recorded from up to 150 stations from the inside and outside. At each station, all visible areas could be measured within 15 minutes.

As a result of this process, data with approximately 90 billion measurement points per church was generated. Such precise scans provide a clear overview of the overall construction. In this way, the building geometry, which is “invisible” at first glance, can be displayed almost like in an X-ray image. The related structure and construction between building components can be quickly recognized.

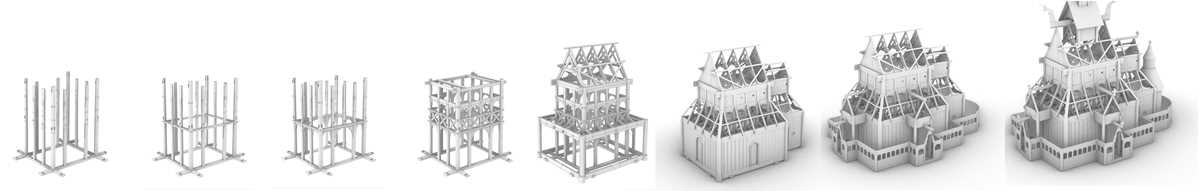

All digital measurements were evaluated at the Chair for Building History, Building Archaeology and Conservation at the Technical University of Munich and converted into CAD drawings and 3D models. In order to understand the work steps in which the church was built, experiments on the construction process were then carried out with digital 3D models.

The results of these experiments are available in these two videos (film 2: Methods and film 3: Results):

RTI-documentation

The details such as wooden surfaces with processing marks from tools, inscriptions and incised drawings were also documented using the RTI (Reflectance Transformation Imaging) method. Each surface to be examined was photographed with 36 photos from radially shifted different angles and illuminated with a grazing flash.

The method makes it possible to make the finest scratches and tool marks visible and thus gain knowledge about the manufacture. For example, a very weakly incised and already heavily weathered rune inscription could be recorded and visualized for the future.

Recording of the decorative stripes on the beam with the RTI method. © Andrij Kutnyi

One of the aims of the project was to use the digital data to decipher the construction sequence in which the stave churches were built by craftsmen. Several references were found in the churches of Borgund, Kaupanger, Lom and Hopperstad.

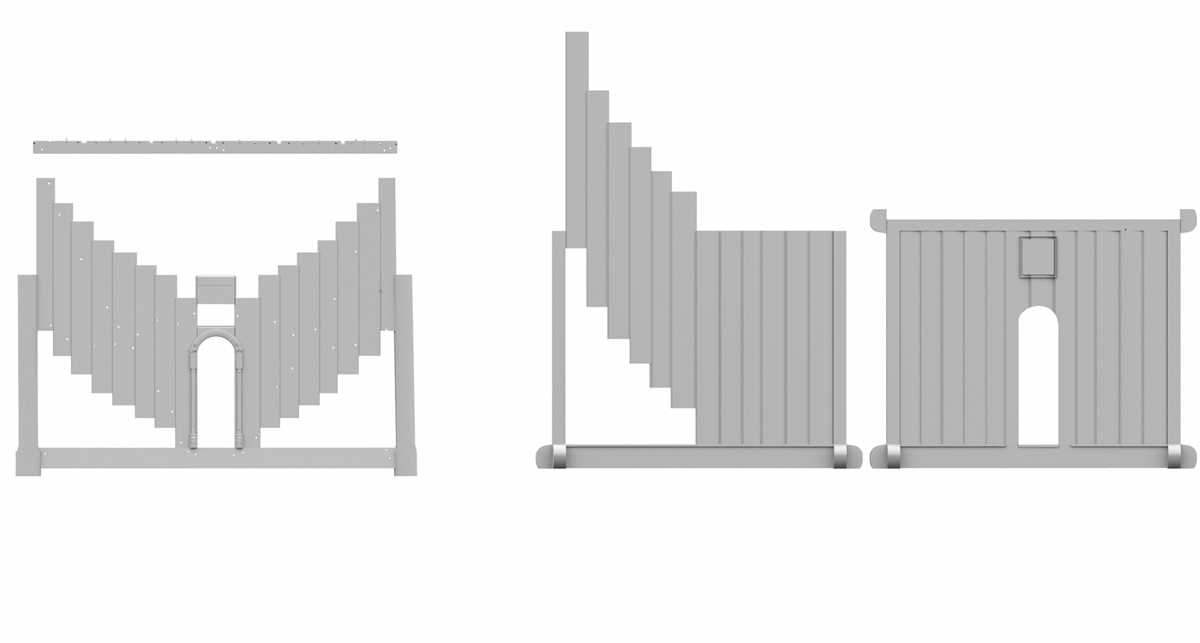

The timber joints between components reveal how the church was built. The connections almost always allow only one way for the components to be joined together. An example of this is the construction of the portal wall. Here, the connections indicate that the wall boards were set up further and further outwards from the door. Similarly, almost all of the compounds could be studied in this examination. This allowed a reconstruction of the building sequence, which is shown in several stages.

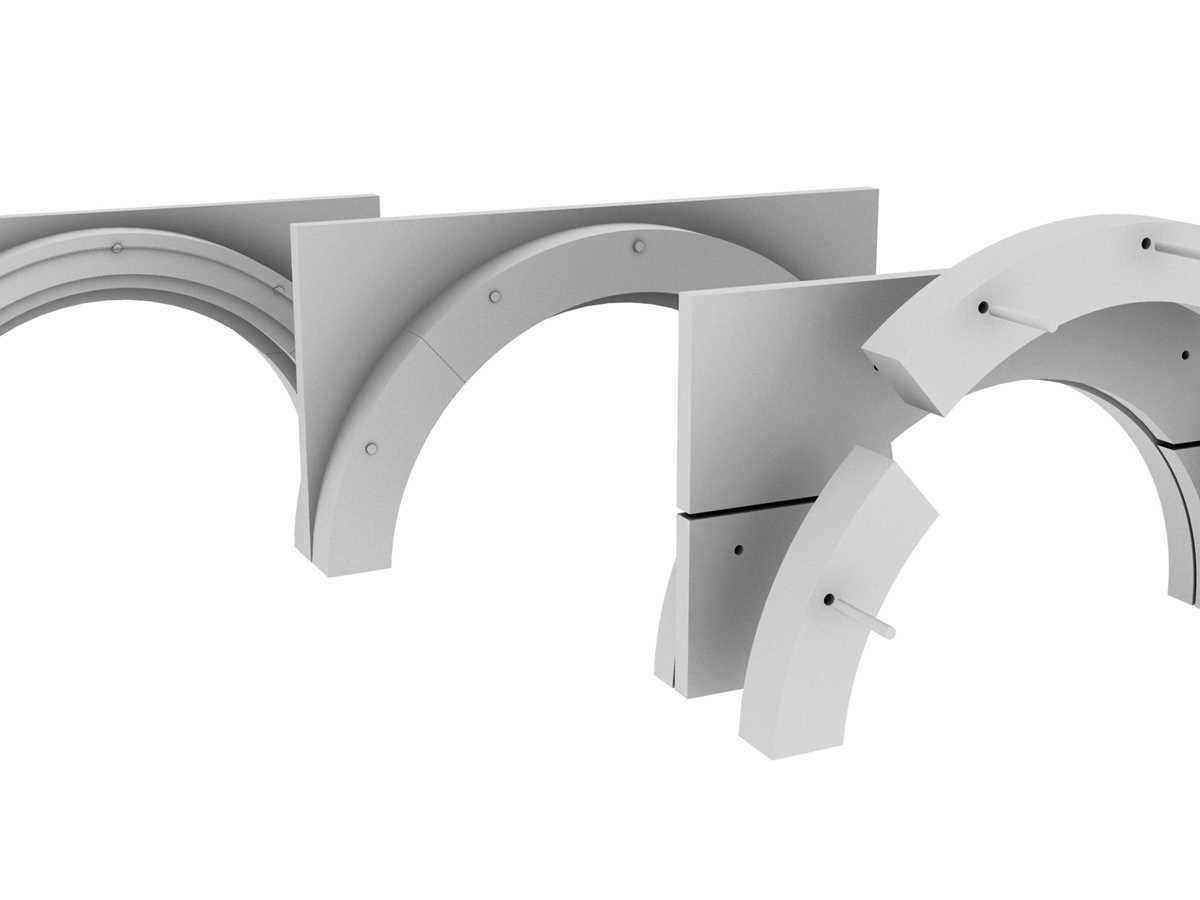

Steps in creating the carved arches in Hopperstad Stave Church. © Andrij Kutnyi

In addition, another piece of evidence was found in Hopperstad, on the arch construction between the columns: the arches were first fixed as blanks in their position between the columns. Only then, from the scaffolding, the step-like decoration was worked out of the wood by craftsmen. Thus, the arches were not carved in detail on the building site outside the church, as it was customary, in order to fix them in the church afterwards.

At the church in Lom, carpenters‘ markings were found on the wall boards, which provide information about the construction method. In Lom, the boards of the north and south walls were built in a row from left to right. In Borgund, the wall structure differs from this. These striking differences in construction suggest that there were originally no door openings in the wall in Lom and they must have been sawn in later in the south and north walls. This measure had taken place with the extension of the church in 1646.

3D-model of the stave church of Borgund (left) and of Lom (right). © Andrij Kutnyi

Such markings were also found in the bell tower (located above the main nave) of the stave church in Kaupanger. Numerous carpentry marks on components that had been created during prefabrication were found here. These symbols were carved to the preassembled tower parts during preparation at the building site. After transporting the individual parts to the church, these should then help to find their positions quickly and assemble the components accordingly.

The examination of the corner connections between all components in Borgund have shown that the main structure, which consists of columns, was built individually (and not as a complete wall). Until now, it was assumed the entire main nave side was assembled in a lying position on the construction site and then tilted. However, this was not possible due to the overlapped corner connections of the horizontal beams below and above the wooden St. Andrew‘s crosses. This means that the columns were set up individually and only after that, further components were assembled from a construction scaffold.

Construction sequence of the stave church of Borgund (simplified presentation). © Andrij Kutnyi

Cultural context

Another focus of the project was the search for traces that provide information about the building tradition and culture of the stave churches. In order to comprehend these traces, some meaningful components of the church buildings of Borgund, Kaupanger, Lom and Hopperstad were examined.

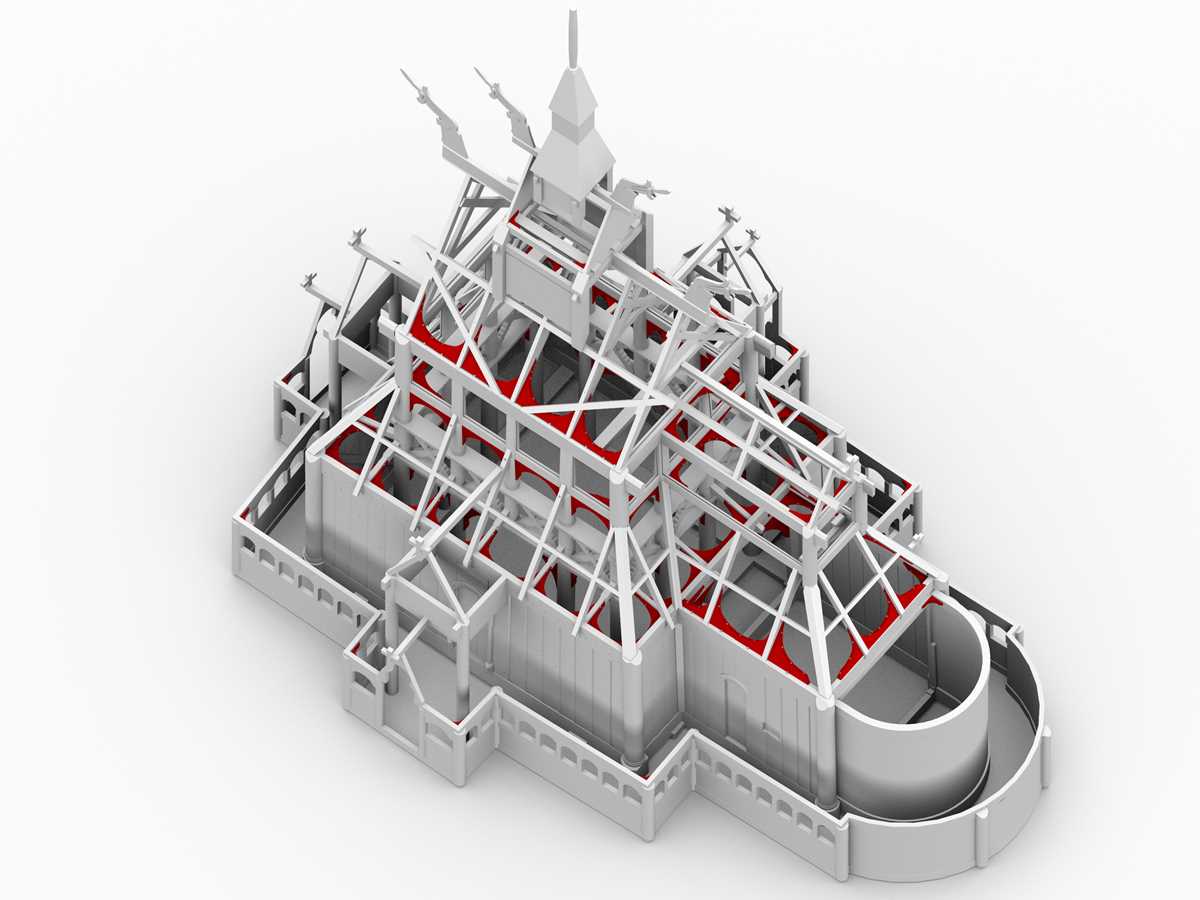

In Borgund, for example, we found a building component that shows a possible relationship to the construction of Viking ships. In all four stave churches, "arched knees" are present as reinforcing structural elements. Nature shaped the material for a building component. Root wood was used in order to produce the knee bracket and some other arcading elements. Two or three brackets could be worked out of one piece of butt end. For the construction of the stave church in Borgund, 154 brackets were needed. This arched knee, which can be found in the churches from a height of two metres up into the roof structure, was also used as a fastening element in ships. The manufacture and shape of the arched knee in all stave churches is identical to the arched knee of the ships.

3D-model stave church of Borgund, highlighted in red: all bow knee components. © Andrij Kutnyi

Even their fastening with a wedged wooden nail, as is known from shipbuilding, has been found in some churches. This connection method in the form of a two-part nail is considered particularly safe.

The investigations have revealed interesting details. It was found that at the stave church in Borgund, more than 10 000 wooden nails were used just to fasten the wooden shingles and over 1200 wooden nails were used to hold the main structure together.

Forty percent of these nails were made with an additional wedge for a more secure hold. Such wooden nails with wedges had been found in large numbers on the Skuldelev Viking ships in Denmark to fasten the bow knee. Over time, wood shrinks and conventional wooden nails could fall out of the component; this wedge, however, enabled a particularly strong and secure connection.

Our calculations showed that it took one worker about twenty working days just to make the nails needed to assemble the wooden shingles on the Borgund stave church.

Wedged wooden nail in Kaupanger. © Andrij Kutnyi

Objects of investigation were also the animals sitting on the pillars of the portals. Two animals in Borgund and numerous examples in other stave churches were examined and documented. They were subjected to an analysis in which their body language and shapes were compared.

It turned out that there is a very great similarity between the animals in Borgund and the animals in Lom. Parallels to the animals of Hegge and Nore can also be made in the development of shapes.

Among other things, the meaning of these figures was also sought. For this purpose, their location was analyzed. Although the church is very small, it has two doors, more precisely two entrances. For a medieval church, a second door into the main room must have been of particular importance, otherwise the loss of heat through a second entrance would have been pointless for the use of the church (for the people).

Carved figures in scale comparison: 1. Ål, 2. Nore, 3. Hegge, 4. Borgund, 5. Lom. © Andrij Kutnyi

In Borgund, similar to Lom, both animals sit at the door leading to one of the oldest parts of the cemetery. They look at the person entering, as if to say, we are testing you for who you are. It is noticeable that the old lock on this door could only be opened from the inside. This could mean that this door could not be opened from the outside due to a fear of returning from the afterlife.

The other related figures from Hegge and Nore show themselves with a fearsome posture by holding a human head in its mouth. By doing so, they are telling us that they can guard this entrance well and do their job.

Kerberos on the portal of the chapel, Castle Tirol. © Andrij Kutnyi

There are different interpretations of what kind of animal it is. They are often referred to as lions or beasts. Our research suggests the second interpretation. These monsters show a physical development that can be derived from the example of the creatures of the stave church in Ål. There the animals have an elongated, writhing body, similar to a lizard. The animal figure by Nore, today hidden under thick layers of paint, also shows a special feature. Here, the agile creature‘s body flows into a tail crowned with a snake‘s head. These formal elements suggest that they are mythical figures that have positioned themselves in an elevated position to protect the entrance.

There are many indications that the mythical Kerberos dogs may originally have served here as an example for the carvers. The iconographic similarity of the motif with the Kerberos on the stone portal from Tyrol Castle is very astonishing.

Click here to explore the researchers' 3D-model of Borgund Stave Church